The Harmon and Harriet Kelley Collection Comes to the Friedman Art Gallery

Misericordia’s Pauly Friedman Art Gallery is showing the Harmon and Harriet Kelley collection of African-American art until April 10. The gallery is open daily from noon to 4 p.m.

The Kelleys, who are based in San Antonio, Texas and who are collectors of African-American art, walked through an exhibition with works created by black artists many years ago. They felt pride over these works but also ashamed they had never heard of the artists. From that point on, they started to collect African American art so their two daughters would never be ignorant of their African American heritage.

The 40 works available on paper date from the 1900s to 2002. The Kelleys selected these works to share African-American history and creativity with the viewers.

This exhibition is extra special to Mrs. Kelley because her nephew, Charles Louis O’Banion, a 2006 graduate of Misericordia University, passed away in 2019.

In this collection, viewers can find a variety of abstractions and naturalistic subjects.

“There’s a wide variety and I hope that people can find an affinity in some of our works,” said Lalaine Little, gallery director.

Little expressed how Misericordia is currently at an important moment historically as a school and community, trying to live up to its mission of inclusion and making everyone feel welcome.

“I want our African-American students to feel that and I want students who are not familiar with African-American art to be able to understand and be apart of this long standing cultural tradition of African-American art,” Little said.

Some of the artists whose works are displayed in the exhibit were practicing during the Works Progress Administration, an ambitious employment and infrastructure program created in 1935 President Roosevelt Franklin D. Roosevelt. The artists were also part of a federal art project created to provide work relief. Artists were employed by the WPA (Works Progress Administration) to create public works of art and to teach classes. The idea was to bring art to the American people during the Great Depression.

“They were trying to improve morale, stimulate the economy, and keep production going during a time that was really tough on folks, economically and socially,” said Little.

Some of the artists of these works were not content with social situations in the United States. Others were part of the great migration of African-Americans from the southern states through the northern states, in hopes of escaping violence, according to Little.

“Part of the response of that movement is evident in these pieces. Those are very striking and some of them are a little bit difficult to confront,” Little said. “I hope that our students have the courage to confront our own past in the United States and how to move forward in a more positive light.”

The Kelleys were adamant about collecting works that reflected African-Americans at work and their goal was to have a good representation of every-day life.

“I loved the costumes, the news boy caps, and the overalls,” Little added. “I loved seeing the ladies in their pearls and Sunday best. There’s something for a lot of different moods.”

In addition to abstractions and naturalistic subjects, works include etchings, lithographs, watercolors, pastels, acrylics, gouaches, linoleum, and color screen prints

Little encourages students visiting the gallery to look at a few pieces in particular.

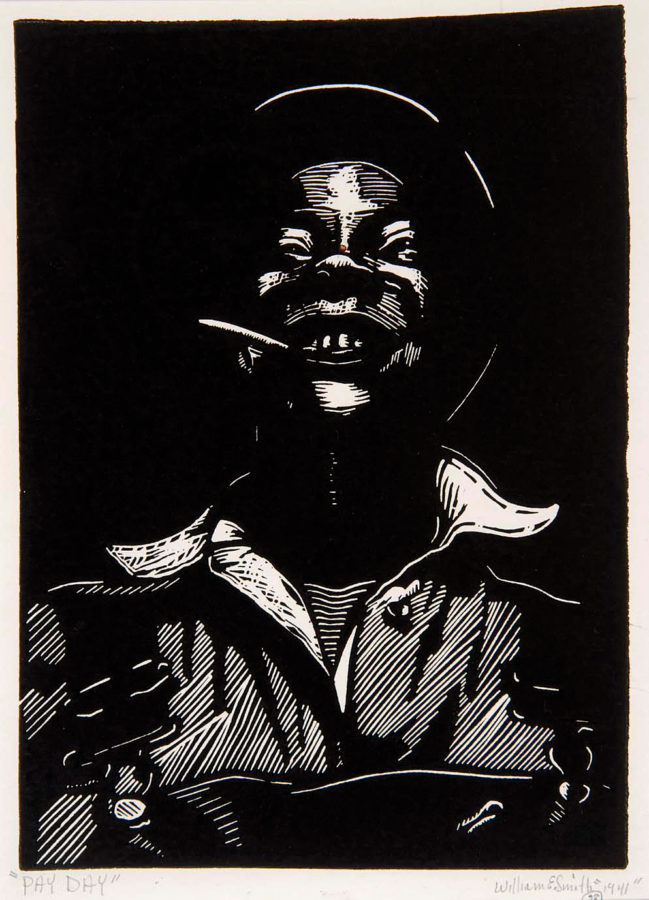

“Payday” by William E. Smith is a favorite among students, according to Little. She described it as a monochrome, black and white work.

“The expression on the subject’s face, people will find a bit to relate to in terms of the title, ‘Payday,’” she said.

Little also noted a work called “Jitterbug” by William Henry Johnson, which she described as lively, colorful, and slightly abstract.

“It uses the space really well where there are sort of arms and legs every-where and it gives you a sense of movement and energy that the jitterbug, of course, encapsulates,” she said.

The last work Little mentioned is a work called “Black Snake Blues” by Alison Saar, a piece Little described as “very colorful and confrontational” and a pivotal piece to have in the gallery.

“It has a snake and a woman, so part of looking at this work is trying to figure out what is going on,” she said. “It’s very striking; it’s brightly colored. This piece is very indicative of the work of Alison Saar; she’s very confrontational about the roles of women, the expectations of especially black women’s bodies.

“What I hope the takeaway for this collection is for people to get a sense of the long history of African American art and the variety of techniques that were explored,” Little added.